You have no items in your cart. Want to get some nice things?

Go shopping

Which skills do my children need to succeed in life?

My house is in complete chaos. How can I make my days smoother?

My child’s behavior isn’t meeting my expectations. What can I do?

Paula Tough, author of How Children Succeed, was curious what kind of influences or conditions made some children do better in life than others. Charlotte Mason asked a similar question in her day: Why do some children never really succeed in life while others flourish?

Is it intelligence?

Parents affluence?

Level of education?

Through they’re extensive research both authors discovered this same answer: character traits like self-discipline, empathy, and positivity are more influential than anything else. Even more than intelligence.

That’s why Charlotte Mason made habits the second instrument of education in her twenty principles.

By “education is a discipline,” we mean the discipline of habits, formed definitely and thoughtfully, whether habits of mind or body.” (Charlotte Mason, Philosophy of Education)

In this episode I discuss the big idea of discipline — why good habits are essential, which ones to focus on, and how to set boundaries in your home.

TRANSCRIPT

Which skills do my children need to succeed in life?

My house is in complete chaos. How can I make my days smoother?

My child’s behavior isn’t meeting my expectations. What can I do?

I’ll answer these questions and more in this episode.

Discipline

The past couple of months I’ve discussed the instrument of atmosphere – the social-emotional instrument of education. Why is atmosphere important? One reasons is that if a person does not feel safe and loved–if the atmosphere is contentious and attachments are insecure–they will not be able to change their behavior or learn. People, and that includes children, will not be able to change their behavior until they feel safe. And behavior, as it relates to character, is the next instrument of education we’ll be diving into. The instrument of DISCIPLINE.

The Sum of Human Nature

Christopher Langen is considered one of the most intelligent people in the world with an IQ score of 195 (for comparison Einstein’s was 150). But he has spent most of his life as a bouncer in a bar and is now a rancher.

Born in 1952, he had access to an adequate education offered by the public schools in Bozeman, Montana. He received a scholarship to Reed college but dropped out and never graduated. When reflecting on his inability to finish college, Christopher Langan explains to Malcolm Gladwell (author of Outliers) that some of the reason was due to financial aid, but most of it was due to experiences that could have easily been solved by good habits and practical knowledge.

All children are born with innate intelligence and desire to be good. But many never reach their full potential even though many have loving parents and access to high-quality education. Paul Tough, author of How Children Succeed, wanted to know which influences in childhood make successful adults. Is it the level and/or quality of education? Affluence? Or something else?

Over 100 years ago Charlotte Mason encountered the same puzzling phenomenon and asked the same question: why do intelligent, inherently-good children grow up to never reach their full potential? In other words, which influences in childhood determine a successful life?

In Home Education, Mason dedicates over 100 pages to answer this question. First, she describes foundational principles of human nature– all the passions, affections and emotions that are common to human beings. Think of it like this: people are born with two opposing forces that temper each other to varying degrees: the Light of Christ and the Natural Man. Every person is born with a unique genetic makeup that influences how they will react to the environment around them–physically, mentally and psychologically.

The sum of all these–The Light of Christ, the Natural Man, and genetics—are what Mason calls “Human Nature.” They greatly determine the character of a child, so much so that parents may think we have little power over our child’s character and the best action is to let them alone. Or, as Mason says, “to let every child develop unhindered according to the elements of character and disposition that are in him.” (Home Education, pg 102) But, human nature must not be left to grow unhindered. Mason clearly predicted the consequence of leaving children to their own devices, she said: “the world is making advances, but the progress is, for the most part, amongst the few whose parents have taken their education seriously in hand; while the rest, who have been allowed to stay where they were, be no more, or no better than Nature made them, act as a heavy drag:” (Home Education, pg. 103).

As influential as human nature is, there is something even more powerful that determines the destiny of a person: their habits.

Let’s go back to Paul Tough and his question: what makes children successful? In his extensive research he discovered that character traits, such as self-discipline, are the most powerful predictor of success. In other words, the habits children gain are more influential than affluence, genetics, and even academics.

‘Habit is Ten Natures’

“The child is born, doubtless, with the tendencies which should shape his future; but every tendency has its branch roads, its good or evil outcome; and to put the child on the right track for the fulfilment of the possibilities inherent in him, is the vocation of the parent.”

It is estimated around 40% of everything we do on a daily basis is habitual. If we had to consciously make decisions about every single thing we did, we would get very little done. Habit is the brain’s efficient solution to free-up working memory and make space for higher level thinking. Habit also takes away the burden of decision making, so the brain can concentrate willpower on more important issues. The vast majority of synaptic connections and pruning happen in the first three years of life. The atmosphere and discipline your child experiences shape their brain in ways that will greatly determine their future.

“By ‘education is a discipline,’ we mean the discipline of habits, formed definitely and thoughtfully, whether habits of mind or body. Physiologists tell us of the adaptation of brain structures to habitual lines of thought, i.e., to our habits.” (Charlotte Mason, Twenty Principles)

Discipline does not mean punishment, it actually means to teach–the essence of discipline is to find alternatives to punishment. Parents discipline by forming habits of body and mind. The goal of discipline is for children to develop good habits and the ability to self-regulate.

Discipline is not Punishment––What is discipline? Look at the word; there is no hint of punishment in it. A disciple is a follower, and discipline is the state of the follower; the learner, imitator. Mothers and fathers do not well to forget that their children are, by the very order of Nature, their disciples. Now no man sets himself up for a following of disciples who does not wish to indoctrinate these with certain principles, or at the least, maxims, rules of life. So should the parent have at heart notions of life and duty which he labours without pause to instill into his children. vol 2 p. 66

Unfortunately, for many of us, discipline is synonymous with threats, bribes, and punishment. But these are employed by parents because they know no other way, or their goal is immediate behavior change. The true goal of discipline should be for children to control their own behavior, and the only way to achieve this is through teaching, setting boundaries, and nurturing good habits. Threats and punishments will never develop character or self-regulation– it ultimately erodes the parent-child relationship, nurtures counter-will/rebellion, and actually weakens the will, or in other words, the ability to self-regulate.

When we say a person is disciplined, we means he acts well of his own desire and willpower, not because someone is forcing him to. Self-discipline does not come from an external force, it comes from within.

Through my research I’ve found that discipline involves two things: setting boundaries and forming good habits.

Setting Boundaries

Children come hardwired to learn. They naturally seek out boundaries and test them. It’s not necessarily because they despise boundaries, they actually crave them. There is a certain comfort that comes with knowing what the boundaries are and the consequences of crossing them. They truly want to know what they ought to do, and what they ought not to do. Why? Because it takes a lot of effort to make a decision. It can actually cause distress when there are too many choices. A load of stress is taken off a child’s shoulders when he knows what choice he ought to make.

Parents must set a few clear boundaries, and exercise their authority ensuring those boundaries are not crossed. Children need to feel that “must” behind making good choices. But this doesn’t mean the parents rule unrighteously with terror.

A healthy parental authority allows a child liberty by teaching him what he ought to do, and showing confidence in his ability to choose what is right. Miss Mason said it this way: “a child has liberty, that is, with a sense of must behind it to relieve him of that unrest which comes with the constant effort of decision. He is free to do as he ought, but knows quite well in his secret heart that he is not free to do that which he ought not.”

In contrast, she said the child who “grows up with no strong sense of authority behind all his actions, but who receives many exhortations to be good and obedient and what not, is aware that he may choose either good or evil, he may obey or not obey, he may tell the truth or tell a lie. And, even when he chooses aright, he does so at the cost of a great deal of nervous wear and tear. His parents have removed from him the support of their authority in the difficult choice of right-doing, he is left alone to make that most trying of all efforts, the effort of decision.”

Young children (before age 8) need much more structure and discipline than older children and teens. Mason said there is a warm flow of goodness at the heart of every young child, but they are incapable of steady effort because they have no strength of will, no power to make themselves do what they know they should do. Young children need the authority and structure that parents provide. You provide this most vital education by your example (atmosphere), structure/routine (discipline), and teaching correct principles (life).

The early years are also called the “formative” years because of how easily children develop habits. Their brains go through synaptic pruning making it extremely easy to pick up habits–good and bad.

Once a child’s will is strengthened and good habits are formed, the parent can slowly step back and let the child govern himself.

This is the function of the parents: to make the child do that which he lacks the power to compel himself to (Home Education, p 99-100). And this is accomplished through discipline.

An essential role of parental authority is making and enforcing rules, or boundaries.

Enforcing boundaries is different than punishing; for example, when your child is throwing blocks enforcing a boundary is telling your child that throwing blocks will hurt someone, and your job is to keep everyone safe so if they choose to continue throwing blocks then they’re choosing to have the blocks taken away, or themselves being removed from block play. Punishment would be spanking your child.

Enforcing will look different depending on the age and situation. But in general, it involves removing your child or the object from the situation. Being the prefrontal cortex for your child while theirs is still developing. Younger children will require a more hands-on approach. For older children enforcing boundaries will be more collaborative.

Here are some things to keep in mind when setting boundaries and enforcing them:

- Less is more. Organize your family’s rules, or boundaries, on a few eternal principles. The more rules there are the harder it is to enforce them all. The best course of action is to teach correct principles (love one another, do unto others, etc) and then have only a few boundaries that kids are not allowed to cross, such as hurting people and harming property.

- If your child continually crosses a boundary, look at the root cause. Instead of continually putting your child in a situation where they don’t have the ability to behave, figure out why they aren’t able to meet this expectation.Do I follow the same rules and boundaries I expect of my children? Are the people my children associate with living the habits and behavior I want my children to adopt? Which skills is my child lacking that are required to meet this rule or boundary? What ideas are they consuming through movies, books, and media that might contribute to their opposition to the boundary or rules of our home?

Lagging Skills

I love the perspective of Ross Greene. In his book, Raising Human Beings, he explains that difficult behavior, or in other words, children that keep crossing boundaries after you’ve taught them what they should do, is simply lagging skills. Some children lack the skills, and habits, to succeed. It’s not an issue of desire or “badness,” they simply need more intentional skill formation. Discipline, therefore, should include identifying and teaching your child the skills they need to succeed. And this starts with getting the child’s will on your side. Both Dr Greene and Charlotte Mason advise working with the child, not on the child. Charlotte gave us an example in her book of a mother instilling the habit of shutting the door. [insert quote]

Ross Greene goes even further and provides a method for parents to cooperate with their child to solve a problem. This method is from his book “Raising Human Beings.” And I find it very effective to combine with habit training.

Train Up A Child

“Every day, every hour, the parents are either passively or actively forming those habits in their children upon which, more than upon anything else, future character and conduct depend. ” (Home Education, pg. 118)

The words “behavior” and “habits” are used interchangeably in this article because they are so closely connected. Behavior either becomes a strong habit by reinforcement, or the behavior goes extinct because it is missing a vital piece of the habit loop (see below). Whether or not a behavior becomes a habit depends on you, the parent.

Children are a bundle of raw material formed from their premortal and mortal attributes, but it is the parents’ job to shape these materials, and the most effective tool is habit training. I love the metaphor of “living clay” to describe parents’ responsibility to instill habits in their children:

“And to him who overcometh, and keepeth my commandments unto the end, will I give power over many kingdoms; And he shall rule them with the word of God; and they shall be in his hands as the vessels of clay in the hands of a potter;”

“How habit, in the hands of the mother, is as his wheel to the potter, his knife to the carver– the instrument by means of which she turns out the design she has already conceived in her brain. Observe, the materials are there to begin with; his wheel will not enable the potter to produce a porcelain cup out of coarse clay; but the instrument is as necessary as the material or the design.” (Home Education, p. 97)

“To help another human being reach one’s celestial potential is part of the divine mission of woman. As mother, teacher, or nurturing Saint, she molds living clay to the shape of her hopes. In partnership with God, her divine mission is to help spirits live and souls be lifted. This is the measure of her creation. It is ennobling, edifying, and exalting.” (Russell M. Nelson, 1989)

Every day you, and the people your child associates with, are shaping your child’s character for good or bad by your habits. In his bestseller book, Atomic Habits, James Clear explores research studies that reveal the social implications of habits. Multiple studies have shown that people of all ages will develop the habits of those around them.

They will more likely develop the habits of the 1) close, 2) the many, 3) and the powerful. If a large number of of peers at school behave a certain way, your child is more likely do develop those habits (the many). If your child is securely attached to someone, they will develop the habits of that person (the close). And if they revere a person, or group of people, they will adopt the habits of that person (the powerful). It is imperative that you understand this truth if you want your child to develop desirable habits.

The habits you should be instilling in yourself and your children should be centered on Christlike attributes. These are the ten habits Charlotte Mason considered the most important:

- Attention

- Obedience

- Truthfulness

- Morality

- Kindness

- Courtesy

- Critical Thinking

- Imagination

- Perfect Execution

- Personal Initiative

Steady Progress on a Careful Plan––Again, the teacher does not indoctrinate his pupils all at once, but here a little and there a little, steady progress on a careful plan; so the parent who would have his child a partaker of the Divine nature has a scheme, an ascending scale of virtues, in which he is diligent to practise his young disciple. … These, and such as these, wise parents cultivate as systematically and with as definite results as if they were teaching the ‘three R’s.’ But how? The answer covers so wide a field that we must leave it for another chapter. Only this here––every quality has its defect, every defect has its quality. Examine your child; he has qualities, he is generous; see to it that the lovable little fellow, who would give away his soul, is not also rash, impetuous, self-willed, passionate, ‘nobody’s enemy but his own.’ It rests with parents to make low the high places and exalt the valleys, to make straight paths for the feet of their little son. vol 2 pg 66-68

Here are some things that make habit training much easier to implement on a daily basis:

- Focus on one habit at a time.

- Be intentional. Habit train during the summer or during breaks so you can fully focus on those habits. Make it the educational focus for that time.

- Start small and be consistent. Compounding interest is the investment principle that small, consistent increases make big payoffs. It is better to have small, but consistent, goals rather than large ones that you cannot sustain. Starting small could be asking your young child to pick up and put away 5 puzzle pieces instead of all of them. Slowly work up to 10, then 20, until they can pick up every single piece. This is similar to the “make it easy” principle—make it attainable.

- Be consistent. The goal is to create a neurological “trail” in your child’s brain that it will automatically take when given the choice. But just like trails in the woods, it requires that the trail is cleared from consistent use. Do your habit as often as possible.

- Decide on “Floors and Ceilings.” How do you implement small and consistent habits? After listening to the “Floors and Ceilings” Brooke Snow podcast episode I started using this concept for habit training, and It has made a world of difference. The floor is the bare minimum, the smallest step you can take. The ceiling is your ideal goal or habit. Decide on your “floor” and your “ceiling” As long as you are doing the bare minimum each day you will keep the momentum going and the habit will form.

- Focus on the process, not the product. Don’t get hung up on mistakes; you’re looking for progress, not perfection. We all make mistakes; the important thing is to look at the process, or pattern, of your habit formation. Slipping up once is a mistake, letting it happen twice in a row is the return to an old habit.

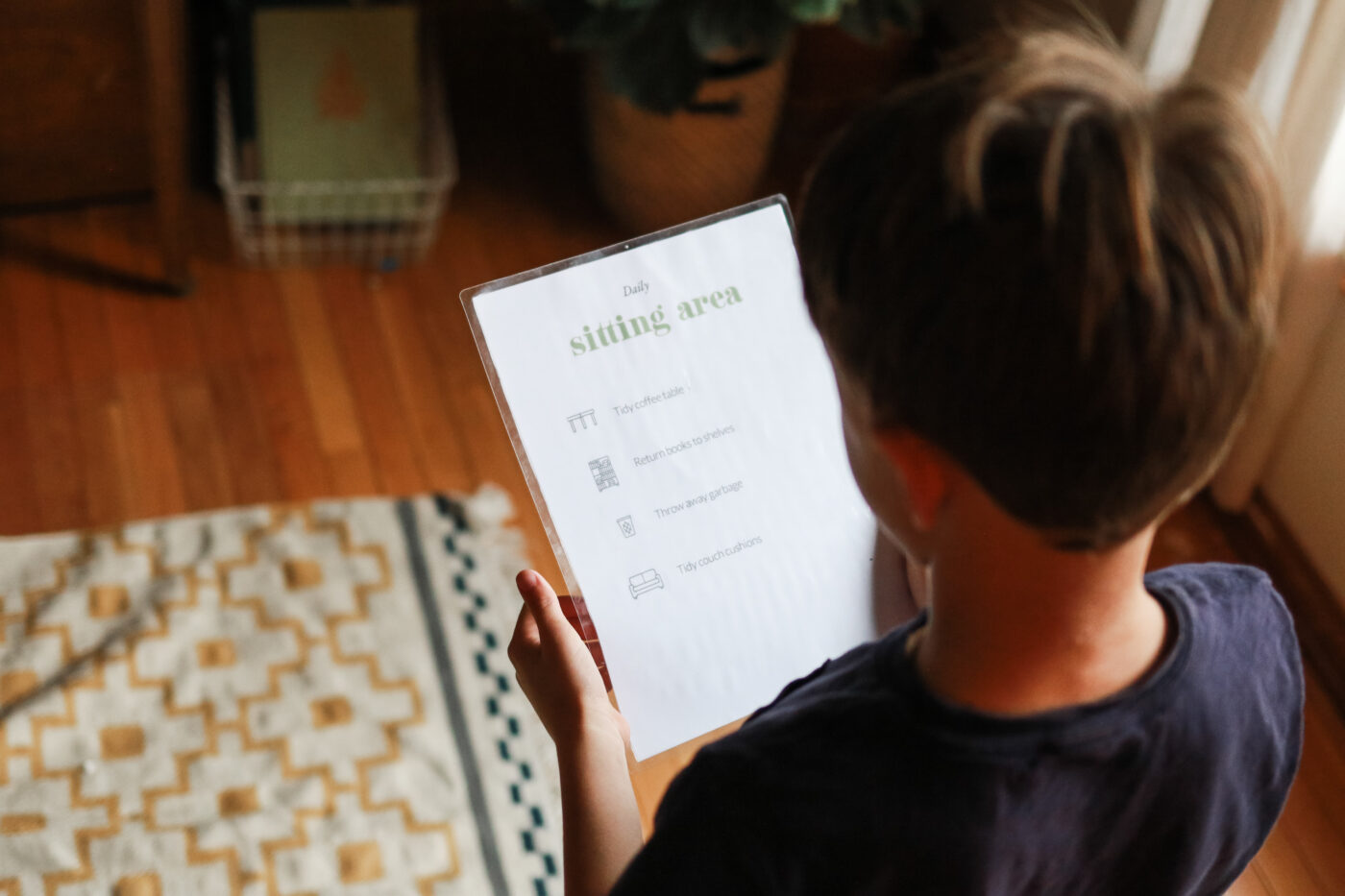

As a parent, you have an enormous responsibility to train up your children with habits that guarantee a happy, successful life. You do this by the beliefs you instill into your children, the words you use to establish their identity, and things you do to reward their behavior. You create a scaffold in the early years while their will is still weak, then slowly nurture good habits so that one day they can govern themselves. As Charlotte Mason famously stated, “The mother who takes pains to endow her children with good habits secures herself smooth and easy days.” (Charlotte Mason)